The opportunity to provide diverse, and high-value, products from this single tree species is at the heart of the eastern black walnut (Juglans nigra) research program at The University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry (UMCA). In general, agroforestry practices place a strong emphasis on creating farming practices that integrate long-term perennial tree crops. This should create a more sound stewardship of natural resources. Black walnut is an ideal tree to meld with existing farming practices because:

- It is deep rooted so as not to be overly competitive for water and nutrients in use by adjacent crops;

- It leafs-out later than most trees and drops its leaves sooner;

- It has a fine leaf that produces a light shade and on the soil breaks down relatively quickly;

- And finally, it offers the potential for high economic returns.

The potential for producing two valuable products from the same tree has captured the imagination of tree planters for years. Both large and small black walnut plantations have been established with the intent to harvest huge nut crops from trees that will eventually produce veneer quality logs. However, if experience has taught us anything about black walnut, it is that optimum nut production and optimum wood production are not normally produced by the same tree.

Indeed, black walnut culture is really the story of two totally different trees all wrapped up into one tree species. The first tree is the walnut timber tree. This tree grows tall and straight in a forest of mixed hardwood trees. Timber-type trees in natural stands, or man-made plantations, are grown closely together with little or no sunlight reaching the forest floor. In these situations, a long, branchless trunk topped by a relatively small canopy of leaves will produce few, if any, nuts. Black walnut timber trees often grow more than 80 years to produce high quality lumber or veneer.

Every black walnut tree grows wood in the form of limbs, trunk, and roots. And as the tree matures, every walnut tree will produce at least a small nut crop. The question is not whether a walnut tree can grow both wood and nuts, but rather which crop you wish to maximize. A focus of UMCA research has been, and continues to be, efforts at understanding the processes which support maximizing economic returns to the landowner while also protecting resources valued by society.

Economic Returns from Black Walnut

What do we really mean when we talk about opportunities to maximize production of a crop? We believe that one of the primary considerations required to sustain natural resources over the long run must recognize that a given practice be economically viable. So, while seeking maximized returns from crop production we are not only focused on generating farm sustaining income, but also keeping resource sustaining agroforestry practices as key elements on the landscape. The point is that if we truly want to protect the environment, then we must also recognize the need for such practices to provide positive income in support of farms.

A Black Walnut Financial Model (BWFM) has been developed by Larry Godsey (Economist for the UMCA) that allows interested managers and landowners an opportunity to manipulate the spacing of a black walnut planting, product prices (timber and/or nuts), and projected growth rates, in order to identify potential returns. This tool is a fill-in-the-blank, Microsoft Excel file that can be downloaded from: http://www.centerforagroforestry.org/profit/walnutfinancialmodel.asp.

The spreadsheet allows a manager or producer to quantify a number of factors that play key roles in profit returns. It can be as simple as filling in the blanks on the input page and scrolling down to view the financial analysis that includes a commentary on: the number of trees per acre and their cost, estimates of final harvest value and board feet, NPV (net present value), IRR (internal rate of return), AEV (annual equivalent value � which is a measure of an equivalent annuity payment), and MIRR (modified internal rate of return).

If you would like to have more control over the input and calculations that go towards the measures of return, then the tabs at the bottom of the Excel spreadsheet allow user input to further guide the calculations. This model can also provide an enterprise budget to the user. By clicking on the Enterprise Budget tab, a printable budget reflecting costs and revenues can be viewed. A cash flow diagram is also available for viewing by clicking on the Cashflow tab. The cash flow diagram will show the NPV, IRR, AEV, and MIRR for each year, along with the estimated revenues and costs.

Because of the simplicity of the model, there are several important limitations that must be taken into consideration. For example, the model is limited to a 100 year time frame. The purpose of the model is to provide an indication of the direction of change for certain management decisions (for example, a closer initial spacing versus a wider initial spacing), and a basis for determining which strategy would work best for a certain site (such as, a site that only grows trees at 0.25 inches per year may be best suited for nut production versus a site that grows trees at 0.5 inches per year). In most cases the default cost structures used in the model are sufficient to achieve the analysis desired, since they are held constant throughout the analysis.

Can we grow the black walnut tree for both wood and nut crops? This model won�t answer that question, and right now the answer appears to be that you do one or the other. However, this model can certainly help landowners see the real value, or cost, associated with practices that place an emphasis on growing black walnut for nuts, timber, or efforts directed towards doing both. The model is constantly undergoing improvements. Larry would certainly welcome input which improves its function. If we are not able to grow a dual-product tree, then a point made by this model is the value of black walnut nuts to economic viability of practices incorporating black walnut trees.

A Summary of Keys to Successful Black Walnut Nut Production

Most black walnut nut research is currently being conducted in an orchard setting. These orchards allow us several advantages, including equal growing space for trees (root and crown space) which maximizes the amount of sunlight, leading to greater nut yields. An orchard tree, by design, normally has a short trunk in comparison to a timber tree, with wide spreading branches, and a full canopy (Fig. 1). Orchard trees are normally grafted using small twigs, called scions that are collected from cultivars with proven nut-bearing characteristics. Nuts can be produced on terminal shoots and also throughout the tree's canopy on short, stout branches or spurs. The orchard tree produces thin-shelled black walnuts that yield the high-quality, light-colored kernels that are able to command top prices in the marketplace. The best grafted orchard trees are precocious, producing nuts within 4 to 7 years of tree establishment, with the first significant commercial harvest starting at about age 10.

The key to success when growing black walnut for nut production is the use of grafted trees. Such trees insure that your black walnuts will exhibit the same character traits as the "superior" tree you collected the scion wood from. However, to realize the gains associated with using such grafted trees one must realize that:

- The grafted tree is growing on a site of similar quality to where the "superior" tree grew (soils, nutrients and water);

- Climatic conditions are similar to where the "superior" tree grew (frost/freeze dates, primarily).

Black walnut trees perform best when grown on deep, well-drained soils. Attempts to establish black walnut trees on shallow soils or excessively wet soils will usually fail. Any soil condition that restricts root penetration to less than 3 feet will ultimately slow tree growth and limit nut production. Walnut trees thrive in soils that range from slightly acidic to slightly basic (pH 6.0 to 7.5) and have a high level of inherent fertility. Problems with pH and low phosphorus need to be corrected during site preparation, along with the removal of competing perennial vegetation, especially tall fescue.

Commercial orchards should only be established on the very best of black walnut sites. These sites are usually found in broad river bottoms where deep, rich soils create ideal conditions for tree growth. Upland sites with deep, fertile soils and excellent water holding capacity also make acceptable orchard sites. Commercial orchards should not be established on sites that tend to be droughty. Lack of soil moisture during the growing season, especially during late summer, will severely affect nut quality and accentuate alternate bearing.

In choosing cultivars for your walnut orchard, review all cultivar traits but keep in mind, there is no "perfect" walnut cultivar that provides all positive characteristics in a single tree. Key cultivar traits include: leafing date, nut weight and percent kernel, disease resistance, and bearing tendency (Table 1). Also realize that many considerations, such as spacing, can play a critical role in overall productivity and timing of potential thinnings.

Health: Looking Beyond Wood and NutsBlack walnut trees are very sensitive to spring frost injury. Freezing temperatures after the onset of budbreak can result in the loss of a tree's entire nut crop. When establishing a black walnut orchard, avoid planting trees in narrow valleys where frost pockets can develop. If you would like to learn more about selecting cultivars specific to nut production, then a recent publication titled Flowering and Fruit Characteristics of Black Walnuts: A Tool for Identifying and Selecting Cultivars will certainly be of interest. You can view the publication at: http://extension.missouri.edu/explore/miscpubs/xm1001.htm.

In today's culture many realities face farmers and their farming practices. one of these realities is that consumers are very health conscious. They like to know where their food comes from, how it's been handled, whether it's organic, and if it is good for them. Consequently, many health conscious people and health/nutrition service providers are now promoting nuts as a component of healthy diets. Many nuts provide a source of unsaturated fatty acids, protein, fiber, and antioxidants, like vitamin E.

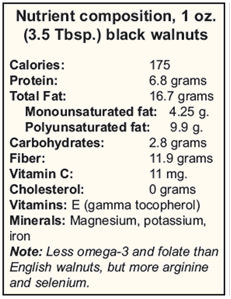

So, how about black walnut? Black walnuts are a unique member of the tree nut family in that they are a source of the omega-3 fat alpha-linolenic acid, one of the "good fats" linked to several important health benefits including lowering cholesterol, regulating heartbeat and reducing inflammation. (Source: Environmental Nutrition, 11/1/2000). Black walnuts are also low in simple carbohydrates and saturated fats, making them a good choice if you're watching your weight (Table Below).

Nut consumption has been linked to a decreased risk of heart disease in several studies. The Adventist Health Study (35,000 participants), and the Nurses' Health Study (86,000 participants), both concluded a lower risk of heart attacks and heart disease for people who ate an ounce or more of nuts a least five times per week. (Source: Food Processing, 11/1/2000). Some healthy tips might include substituting black walnuts for a handful of chips at lunchtime, or try black walnuts on salad instead of cheese.

Ongoing Research and A Vision Towards the Future of Black Walnut

There are a number of advantages to growing black walnuts, for either timber or nuts, and although we know a lot about this valuable, native species, many such "grower questions", especially for orchardists, remain to be answered. Such as, is it possible to improve this species through traditional plant breeding techniques to improve nut yields? So far, the answer is "yes", based on a 13-year-old breeding program designed to improve both nut yields and adaptability over the long run. This program will ultimately lead to the development of improved black walnut cultivars. The future looks very promising for this program since the majority of the black walnut nut cultivars we work with exhibit high levels of genetic variation for all of the commercially important traits we have looked at, such as spring leafing date, percent kernel, season length, etc.

In addition to our ongoing breeding program, which is just now entering its second generation of selection, other "grower questions" that focus on traditional orchard practices such as pruning, irrigation, fertilization are being, or soon will be, addressed. For example, we will be establishing a series of plantings in 2011 that is designed to quantify the influence of different rootstock origins on performance of young grafted trees in new orchards. We will also be addressing questions such as the effects of harvest date on kernel color and quality, as well as the causes of alternate bearing and the identification of sources of disease resistance in this species.

The future of growing black walnut is very promising and we encourage you to first seek out information on how to set up new orchards or timber plantations in order to maximize your chances for success. In addition to the resources listed in this article, you may want to consult the web-based resources of the Walnut Council (http://www.walnutcouncil.org) and also the Northern Nut Growers Association ( http://www.nutgrowing.org) for additional information.

This article has been adapted from publications developed by, or in collaboration with, The University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry. Please feel free to visit the following websites to read more on any topic we have covered:

- Growing Black Walnut for Nut Production

- Economics of Black Walnut Nut Production: Black Walnut Financial Model - http://www.centerforagroforestry.org/profit/walnutfinancialmodel.asp

- Nutrition and Your Health: Why Black Walnut - http://www.centerforagroforestry.org/pubs/whywalnuts.pdf

Or, you may feel free to contact the authors of this article:

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Research Analyst

MU Center for Agroforestry

203 ABNR

Columbia, Missouri 65211

573-884-1777

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Senior Research Specialist

MU Center for Agroforestry

203 ABNR

Columbia, Missouri 65211

573-884-7991